BOBOLINK COFFEE IN GERMANY BY KAFFEERÖSTEREI

December 12, 2018

BOBOLINK COFFEE IN GERMANY BY KAFFEERÖSTEREIDecember 12, 2018

La Torref De FersenNovember 19, 2018

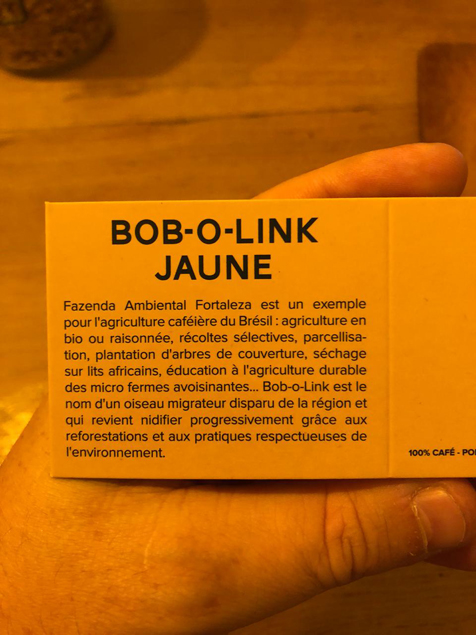

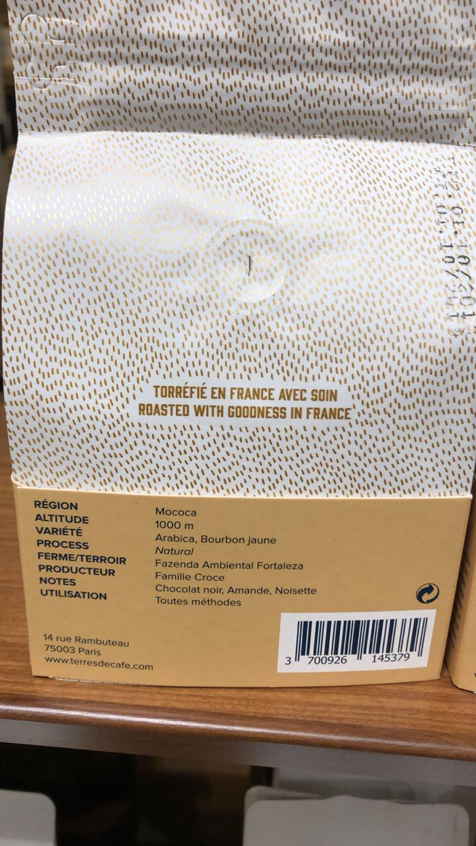

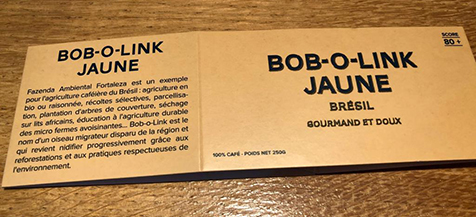

Terres de Café — ParisNovember 9, 2018

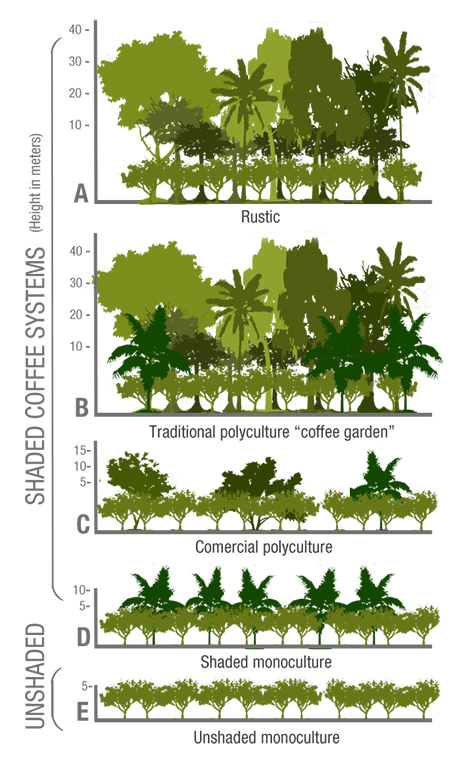

SHADE-GROWN COFFEE: WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL?November 05, 2018If you bought a cup of certified coffee recently, chances are good it might have been brewed using "shade-grown" beans. But what is shade-grown coffee exactly, and why is it important? What does shade-grown coffee look like?Coffee can be grown under shaded or full-sun conditions. Globally, about 25 percent of the world’s coffee land is managed under diverse shade, 35 percent under partial shade, and 40 percent under full-sun. The amount of coffee land under full-sun conditions has increased dramatically over the last half-century, as many have sought increased yields via full-sun plantations in newer areas such as Brazil and Vietnam, and the conversion of shade-grown farms in Latin America.

Coffee grown under full-sun conditions | Photo credit: Tico Times

Versus coffee grown under partial shade conditions Many coffee tree varietals, however, naturally prefer shaded environments, such as the tropical rainforests of Central or South America. This is particularly true of Arabica trees, which provide most of the world’s specialty coffee. As a result, many farmers continue to grow their coffee trees within natural or managed forest landscapes, a practice known as “agroforestry,” generally beside deciduous shade and/or fruit trees. Coffee produced on agroforestry farms is broadly referred to as “shade-grown coffee.” However, not all shade-grown coffee is the same. The extent of shade coverage in agroforestry systems varies widely, from densely shaded systems resembling mature forests to more lightly shaded systems with only one or two varieties of shade trees. Generally, agroforestry farms can be grouped into the following three categories:

Adapted from Moguel, P., and Toledo, V.M. (1999). Why is agroforestry coffee important?Shade-grown coffee can benefit farmers and the environment: Potential Livelihood Benefits:

Potential Environmental Benefits:

How does agroforestry relate to Root Capital’s portfolio?The majority of Root Capital’s coffee clients buy from farmers growing shade-grown coffee, generally from traditional or commercial polyculture systems. Many of these clients help farmers maintain or further diversify their agroforestry farms by providing them with training on shade management, or with free or subsidized shade tree seedlings. (We collect this information using our Social and Environmental Scorecards.) Our loan officers have conducted due diligence on agroforestry coffee farms in the jungles of Peru, the cloud forests of southern Mexico, the volcanic hills of Uganda, and everywhere in between. BOBOLINK COFFEES IN PARISOctober 31, 2018

FELIPE CROCE ON SUSTAINABILITY IN THE COFFEE SECTOR AND SPECIALTY COFFEE CULTURE IN BRAZILOctober 12, 2018

Since 1850, Felipe Croce’s family has been producing coffee at Fazenda Ambiental Fortaleza (FAF), an organic coffee farm located in Mococa, on the east side of the state of São Paulo in Brazil. His mother, Silvia Barretto, became the fourth generation to inherit the farm when it was passed down to her in 2001 by her father. The Croce family was living in Chicago at the time, and they found specialty micro-roasters in the city that were eager to work directly with farms. Felipe’s father, Marcos Croce, an international trader, began to look for buyers. His mother had a vision for an organic, sustainable coffee business, so they put special focus on consideration for the environment and building strong relationships in the supply chain, while producing high-quality products.

Marcos Croce and Silvia Barretto at Fazenda Amiental Fortaleza. Photo courtesy of Felipe Croce. According to Felipe Croce, FAF was a relatively high-quality and high-producing farm in the 1990s — producing around 10,000 bags of washed and naturals sold mostly to Illy under his grandfather. When his parents took it on, they decided to decrease the production of the farm drastically to learn how to adapt to organic practices and higher quality. Felipe moved to the farm in 2009, after attending Washington University in St. Louis, and ran the farm’s operations from 2009 to 2012. In 2013, he moved to the city of São Paulo and switched his focus to the export company and his lab, while continuing to conduct experiments on the farm. His mother took over management of the farm at that point. Last year, Felipe resumed a more active role in the coffee production, going out to the farm once or twice per month. He is currently in the process of restructuring all the lots on the farm by making field spacing adequate for mechanization, and choosing the most appropriate varieties in terms of flavor and results. We asked Felipe to share some thoughts and give his perspective on sustainability, Brazilian specialty coffee, and the growing domestic market in Brazil in the world’s largest coffee-producing country.

Fazenda Ambiental Fortaleza Fazenda Ambiental Fortaleza. Daily Coffee News photo/Lily Kubota. Lily Kubota: What do you see as the biggest opportunities and challenges for specialty coffee in Brazil? Felipe Croce: I see huge potential for Brazil to supply the growing demand for specialty beans. However, this will only happen with a radical change in how coffee is done in the country. On the production side, new varieties need to be studied. Shade and green fertilization techniques need to be implemented to keep temperatures down, humidity up, and soils fertile. The business models of associations and warehouses — and the “business language” of coffee in Brazil — are archaic and commodity-oriented. Actions are rarely bold enough, and change can seem to take forever. An educational platform for farmers would go a long way to accelerating and solidifying Brazil’s place as a premiere specialty coffee supplier. As for roasting and consumption, we are positioned to have one of the biggest consumption markets in the world in the next five to 10 years. I see the potential of a brand from origin establishing itself as one of the leading specialty brands globally. Lily Kubota: From your perspective, how has the coffee industry evolved in recent years, and where do you see it going? Felipe Croce: More than ever, producers are tasting their own coffees — with good roasts and proper extractions — and beginning to look at their coffee as a beverage. Many producers are starting to roast and increase their income, at least on a portion of their production. There are new regions being ‘discovered,’ and farmers and roasters are establishing relationships. Change is slow at first, but as specialty culture begins to gain traction in producing regions, it will take off. Until around 2010, the only two coffee varieties planted in Brazil were Typica (arrived in 1727) and Bourbon (arrived in 1840), or derivatives of these. Now, more and more farmers are experimenting with different varieties. At my farm, for example, I have more than 30 different types of Coffea Arabica genetic material. On the consumption end, the interest in specialty coffee is growing — I am seeing specialty cafes packed with 18-to-35-year-olds, from San Francisco to Melbourne to Seoul to Paris to São Paulo. Coffee is in with young people, and it’s only getting better.

Felipe Croce at La Marzocco Booth Felipe Croce brewing coffee at the La Marzocco booth during the SCA Expo in 2014. Photo by Baratza. Lily Kubota: You are also are involved with the retail side of coffee. When did you decide to open a cafe? Felipe Croce: I started roasting in São Paulo in 2013 — partly to have an excuse to spend more time in the city, but also because of a genuine passion to convert Brazilians into ‘good coffee’ lovers. I have been extremely fortunate to be supported by an incredible team of dedicated people, and we had always dreamed of opening a shop to showcase what we do. In 2015, this was accelerated by the invitation of a well-known entrepreneur by the name of Facundo Guerra, who is known in São Paulo as the ‘King of the Night’ from his nightclub, bar, and restaurant endeavors. Facundo had taken over a space wedged between a tunnel and a bridge, which had been abandoned for 78 years, just meters away from MASP (Museum of Art of São Paulo), the most iconic building in the city. The space was coined Mirante 9 de Julho and became a cultural center for arts, music, cinema, gastronomy, and coffee. Although we are involved in all aspects of coffee, we focused on serving delicious coffee and kept our communication as simple as possible, calling it Isso é Café (This is Coffee), because we knew the public was not ready for too much information in the beginning. We gained a strong following and good reputation. Our second shop opened in May of 2017, in what is perhaps the next most iconic site in the city, Beco do Batman (Batman Alley), where the most unique and diverse graffiti in São Paulo is found. Lily Kubota: What are your future plans on the retail side? Felipe Croce: In a bold move, we have decided to close both (profitable) cafes to open a 400-square-meter all-in-one roastery, export office, cafe in the city center. We have decided, in fact, to stick with only one retail space and bring our three entities — farm production, export team, roastery/café — closer together. The new space will have a cocktail bar and kitchen, which we want to use to highlight ingredients from our farm and surrounding areas, including pigs from one neighbor and cachaça (Brazilian sugar cane distilled alcohol) from another neighbor. Lily Kubota: What have been the most valuable or influential resources that have helped you learn about coffee? Felipe Croce: Being a sponge. My father always said, if this is what you want to do, then go and learn from the best. From 2010 to 2012, I spent half of the year on the farm and half of the year abroad somewhere learning, working, and trying to expand my network. I spent time with the likes of Tim Wendelboe, Johan Eckfeldt, Mike Perry, Mark Dundon, Russell Beard, amongst other industry legends. I also read a ton and visited as many farms as I could. Each person has something to teach you, but the best in the business just have something natural in them — something about their vision gave me a North Star. Lily Kubota: From your perspective, what are the most critical aspects regarding sector-wide coffee sustainability? Felipe Croce: We need to make sure that knowledge and opportunity are spread equally across the supply chain. I hope that access to good seeds, the market, and information will become more widely available to small farmers and small business owners, so that we don’t see too much control concentrated in the hands of a few. Entrance to Fazenda Ambiental Fortaleza. Photo courtesy of Felipe Croce.

Three Questions with Felipe Croce Lily Kubota: What inspires you most about coffee? Felipe Croce: The challenge. The challenge to increase soil fertility, improve water quality, increase production, and run a profitable business at the same time. The challenge to ensure that each cup tastes great, while the bean flirts with death on any of the dozens of steps involving dozens of people on its journey. Lily Kubota: What troubles you most about coffee? Felipe Croce: Having patience. Things on the farm take time. We must be patient when it doesn’t rain, and when it does rain. Things don’t always go as planned. Not all espresso comes out perfectly. We must have patience with the process. Lily Kubota: What would you be doing if it weren’t for coffee? Felipe Croce: Real estate. I once did a mentorship program in real estate back in Chicago and found the business fascinating. It has a similar nature to coffee in terms of mixing creativity, risk, and long-term thinking. Something about the fact that it is real, tangible — brick and mortar — is incredibly sexy to me. BOBOLINK PROJECT - SERRA DO CIGANOApril 2, 2018

Picture from London Stanstead airportAugust 2018

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Created by UniverDesign | Powered by www.atimo.us | E-system | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||